This section hasn't been started yet It is a placeholder for future work.

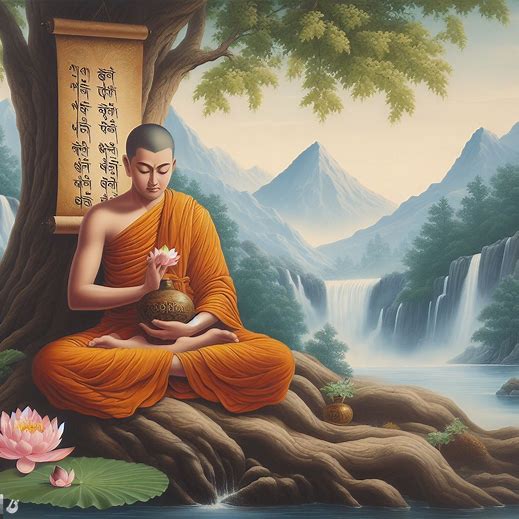

The Four Noble Truths

The Final Stages of Understanding the Four Noble Truths

The Tathagata’s teaching on the Four Noble Truths is not merely theoretical; it is a path of direct realization, unfolding gradually and culminating in complete release. In the final stages of understanding, the disciple sees directly into the nature of suffering (dukkha), its origin, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation. This article outlines this process as described in the early discourses (Nikāyas), focusing on how cognition itself is seen as conditioned suffering, and how relinquishment (paṭinissagga) and cessation (nirodha) bring about liberation.

The Four Noble Truths are:

-

The Noble Truth of Suffering (Dukkha)

-

The Noble Truth of the Origin of Suffering (Craving, Taṇhā)

-

The Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering (Nirodha)

-

The Noble Truth of the Path leading to the Cessation of Suffering (Magga)

At the mature stage, these are no longer intellectual propositions. Instead, as the Tathagata says:

When a noble disciple fully understands suffering, fully understands its origin, fully understands its cessation, and fully understands the path leading to its cessation, they are called one who has entered the stream of the Dhamma.

SN56.11

Seeing All Cognition as Dukkha

In deep insight, the disciple observes that all conditioned phenomena (saṅkhāra), including cognition itself, are impermanent (anicca), unsatisfactory (dukkha), and not-self (anattā).

The Tathagata explains:

Whatever is felt is included in suffering.

SN36.11

Cognition, perception, feeling, all arise dependent on contact (phassa), which is conditioned by name-and-form (nāma-rūpa) and consciousness (viññāṇa). Each moment of cognition contains dukkha because it carries the seed of craving, becoming, and clinging.

As one sees this, disenchantment (nibbidā) arises:

Seeing thus, the instructed noble disciple becomes disenchanted with form, feeling, perception, volitional formations, and consciousness. Disenchanted, they become dispassionate. Through dispassion, the mind is liberated.

SN22.59

The Process of Letting Go: Dispensive Dispatching (Paṭinissagga)

At this stage, the disciple doesn't merely suppress cognition or sensory experience but relinquishes attachment to them.

The Tathagata uses the term paṭinissagga, giving up, letting go:

This is peaceful, this is sublime, the stilling of all formations, the relinquishing of all acquisitions, the destruction of craving, dispassion, cessation, Nibbāna.

MN64

Paṭinissagga is not forceful rejection, but a natural falling away of clinging when one fully sees the conditioned nature of phenomena. The mind ceases to grasp at any experience, including the subtlest mental formations.

Cessation: The Ending of Cognition as Suffering

When craving is fully abandoned, cessation (nirodha) follows. This is not annihilation of being, but cessation of the fuel that sustains suffering. The Tathagata describes:

With the cessation of craving comes the cessation of suffering.

SN56.11

In some discourses, this is presented as the cessation of perception and feeling (saññāvedayitanirodha), where even the subtlest mental processes temporarily cease. Yet this is not necessary for full awakening; what is necessary is the cessation of clinging.

The arahant lives experiencing the world but without appropriation:

Having nothing, not taking up anything, they dwell with a mind free, unbound, liberated.

UN8.1

The Fruit: Liberation and Unshakeable Peace

With full realization of the Four Noble Truths, the mind is unshakably free:

Birth is destroyed, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more coming to any state of being.

MN26

The arahant sees phenomena arising and passing without the slightest craving or resistance. Cognition continues as functional but no longer as a basis for self or suffering. This is true freedom.

The final stages of understanding the Four Noble Truths are not about annihilation or withdrawal but about seeing directly the nature of all conditioned phenomena and releasing any basis for craving. As the Tathagata repeatedly states, "Nothing whatsoever is to be clung to."

SN56.42: The Blessed One, while at Rajagaha on Vulture Peak, led disciples to Paṭibhānakūṭa. There, a disciple pointed out a frightening chasm, prompting a discussion on a metaphorical chasm more daunting: ignorance of the true nature of suffering and its cessation. The Tathagata explained that misunderstanding the nature of suffering leads to mental formations that perpetuate birth, aging, death, and despair. Conversely, understanding these truths prevents the creation of such formations, freeing one from this cycle of suffering. The Tathagata emphasized the importance of recognizing and understanding the nature of suffering to achieve liberation.

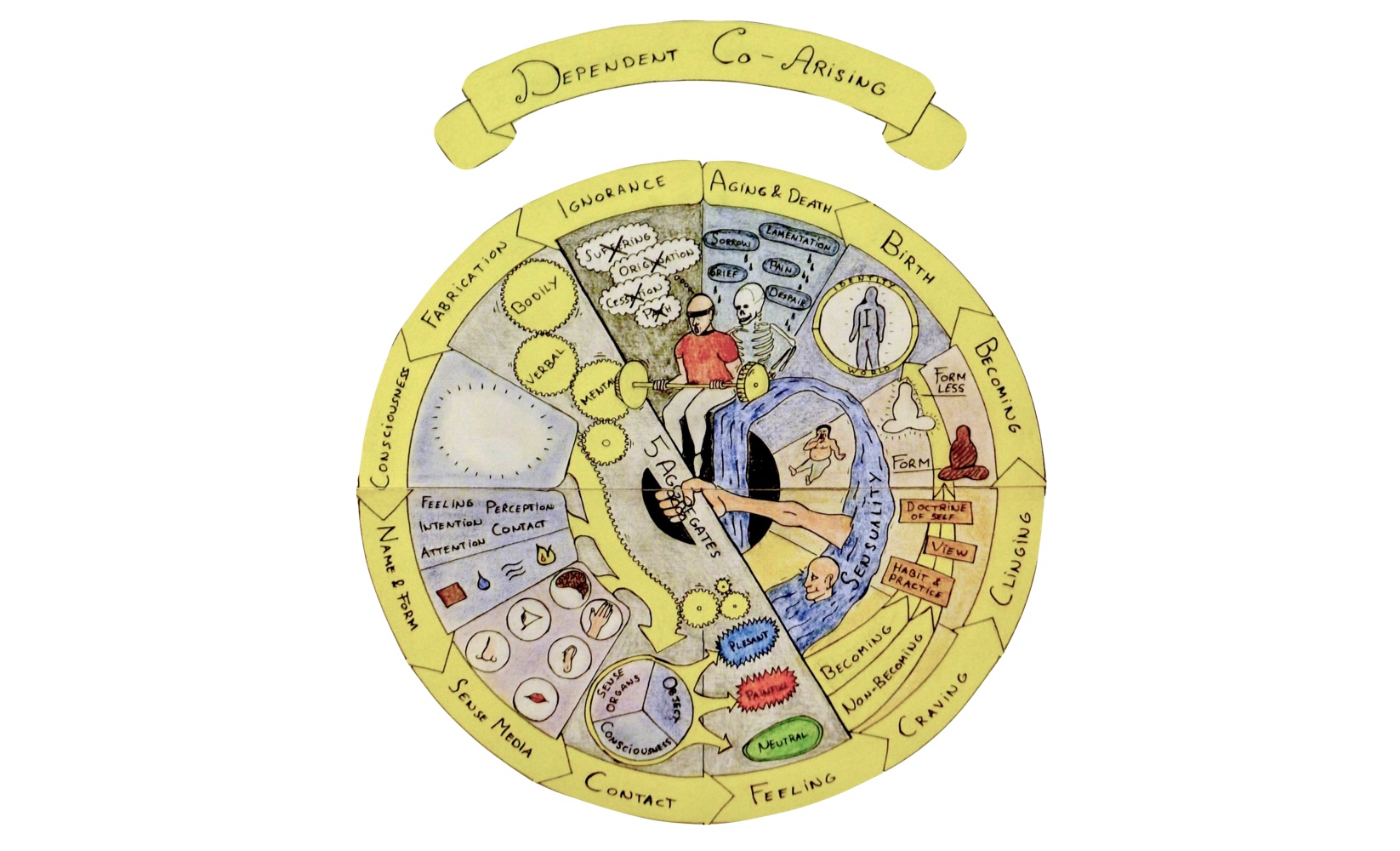

Dependent Origination Understood Through the Analogy of a Computer

Ignorance (Avijjā) – The Root Virus in the Operating System

Ignorance is the core malware, embedded deep within the system. It distorts the computer’s basic logic, how it interprets inputs and outputs, so that the user doesn’t even realize the system is compromised. This is saṃsāra: a mind infected with greed, aversion, and delusion, not realizing that these programs generate endless suffering.

Not knowing suffering, not knowing the origin of suffering, not knowing the cessation of suffering, not knowing the path leading to the cessation of suffering—this is ignorance.

SN12.2

Volitional Formations (Saṅkhārā) – The Background Processes

Volitional formations are the background processes that ignorance starts to spawn, automatic reactions, pre-programmed biases, and unexamined impulses. They generate intentional actions of body, speech, and mind. Over time, these processes install karmic patterns, like mental “code” that conditions how future experiences are rendered.

With ignorance as condition, volitional formations come to be.

SN12.2

Consciousness (Viññāṇa) – The 3D Graphics Processor

Consciousness is like the graphics processor that renders what is displayed on the screen, transforming unseen digital code into the living 3D world of experience. It doesn’t create or own the content; it merely displays what arises from the interaction between software (nāma) and hardware (rūpa).

Consciousness is reckoned by the particular condition dependent on which it arises.

SN22.79

Name-and-Form (Nāma–Rūpa) – The Software Interface to the Hardware

Rūpa (form) is the hardware: the body, circuitry, sensory organs, and physical processes. Nāma (mind functions) is the software: attention, feeling, perception, intention, and contact.

Together, nāma–rūpa forms the operating system layer that allows the mind and body to work together. It takes in input from the physical world, converts it into experience with the help of consciousness, and renders a “world” on the screen of awareness.

The virus of greed, hatred, and delusion is deeply embedded in both name-and-form and consciousness, ready to infect any input that arises.

Consciousness and name-and-form are interdependent, like two sheaves of reeds standing and supporting each other.

SN12.67

Six Sense Bases (Saḷāyatana) – The Input Devices and Digitizers

The external sense bases, camera (eye), microphone (ear), chemical sensors (nose and tongue), touch sensors (body), and the internal processor (mind), gather data from the world. The internal sense bases process this information into signals the system can interpret, sights, sounds, tastes, tactile sensations, odors, and thoughts.

Contact (Phassa) – The Digital Data Exchange

Contact occurs when a sense organ, its object, and consciousness align, like a data handshake between a camera, a driver, and a processor. When you take a picture and see it displayed, contact is that moment the raw input becomes meaningful data.

Dependent on the eye and forms, eye-consciousness arises; the meeting of the three is contact.

SN35.93

Feeling (Vedanā) – The Reaction to the Feed

Each contact produces a feeling tone, pleasure, pain, or neutrality. This is the initial emotional “feedback” from the data stream. Perception and recognition follow, creating impressions about what has been experienced.

Craving (Taṇhā) – The Urge to Seek More Stimulation

From pleasant feelings, craving arises.

Craving is the active virus code that continually seeks to embed itself in each experience. The user wants more of what pleased them, more excitement, attention, stimulation, or wants to escape the unpleasant.

So they post, share, consume, and seek, hoping each experience will generate that next “click” of pleasure or validation. The virus uses this to keep the system engaged: more scrolling, more seeking, more input.

Dependent on feeling arises craving.

SN12.1

Clinging (Upādāna) – Becoming Enmeshed in Each New Pursuit

Craving solidifies into clinging when the user starts to identify with the content they pursue. They say, “This is my lifestyle, my interest, my passion.” They dive into each fascination, motorcycles, cuisine, travel, fashion, relationships, spirituality, convinced, “this time it will fulfill me.”

Like a user trapped in trending loops, they become caught in cycles of self-definition, mistaking each phase for who they truly are.

Becoming (Bhava) – Living Fully in Each Temporary Identity

Each attachment crystallizes into a temporary identity, the “motorcycle rider,” the “chef,” the “traveler,” the “yogi.” They build relationships, routines, and meaning around that role. This is becoming, the psychological and karmic formation of a new personal world. Yet every identity is conditioned by craving and thus inevitably unstable.

Birth (Jāti) – The Rise of a New Self-Image

When one identity collapses, another is born. He moves from motorcycles to photography, from ambition to minimalism, from romance to renunciation. Each feels like a fresh start, but in truth it’s only another running process of the same infected operating system. The ignorance, virus ensures that the cycle continues, always chasing, always beginning again.

Aging and Death (Jarāmaraṇa) – Disillusionment and Burnout

Every pursuit fails to satisfy. The excitement fades, the illusion breaks, and the self-image dies. There’s disappointment, confusion, grief, and then the craving to find something new arises again.

Thus, saṃsāra is not merely rebirth between lives; it is the continuous rebirth of “selves” from moment to moment, as the mind chases satisfaction through impermanent experiences.

Liberation (Nibbāna) – Seeing the Process Clearly

When one observes this endless cycle with wisdom and mindfulness, without judgment or identification, the virus loses power. Craving ceases. The compulsion to “be someone” dissolves. One no longer needs to chase or escape; the system falls silent. This is Nibbāna: the end of the program, the uninstallation of the malware, freedom from all craving.

When a noble disciple understands dependent origination and its cessation, they are freed from suffering here and now.

SN12.15

True Nature of Conciousness

Now, let's review:

-

The only thing we know in this world is consciousness, which consists of five aspects: form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. These five aspects are referred to as the Five Aggregates. The characteristics of the Five Aggregates are that they are conditionally arising, impermanent, conditioned, subject to change, ownerless, not self, and not belonging to a self. This is the true nature of the world.

-

Consciousness is the result of the interaction between the senses and objects in the mind. When consciousness arises, the senses, objects, and consciousness together form a person, sentient being, or life. If the arising consciousness is ignorant of the true nature of the world, it may develop tendencies of liking or disliking due to its experiences of suffering, pleasure, or neutrality. These tendencies are accompanied by thoughts of greed or aversion. Just as a tilted flame can ignite nearby flammable objects when blown by the wind, these thoughts can lead to the arising of new senses and objects, resulting in the rebirth of consciousness and life.

-

If consciousness arises with complete awareness and mindfulness, there will be no tendencies of liking or disliking. Without corresponding thoughts, new consciousness will not arise, leading to the cessation of consciousness or life.

-

If people understand that giving, observing ethical conduct, and performing virtuous or unvirtuous actions lead to corresponding consequences in this life and the next, and that there are cycles of rebirth in virtuous and unvirtuous paths, as well as methods to be reborn in virtuous paths or attain liberation, they will strive to regulate their speech and behavior, engage in virtuous deeds, and avoid unvirtuous actions. They will find inner peace and fearlessness by recalling the good deeds they have done. This inner peace will lead to joy, a willingness to listen to virtuous teachings, with the teachings of the Buddha being the most revered. By frequently listening to the teachings and contemplating the Four Noble Truths, individuals will aspire to realize them personally. To achieve this, people may renounce worldly life, isolate themselves from distractions, cultivate virtue, and eradicate unwholesome behavior.

By dwelling in mindfulness and clear comprehension, overcoming the five hindrances of desire, aversion, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and doubt, individuals will experience joy, attain the first jhana, and progress to the second, third, and fourth jhanas. The mind in the fourth jhana is like a fire without wind, impartial, steady, free from greed, aversion, and delusion, understanding the arising and ceasing of consciousness, and attaining self-liberation.

Therefore, for anyone seeking liberation: 1. Understand the true nature of consciousness. 2. Understand and eliminate the conditions that give rise to consciousness. 3. Understand and realize right knowledge and liberation. 4. Understand and practice the Eightfold Path of right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

There are, Ananda, seven stations of consciousness and two realms. What are the seven? There are beings diverse in body and diverse in perception, such as humans, some gods, and some beings in states of woe. This is the first station of consciousness.

There are beings diverse in body but uniform in perception, such as the gods of Brahma's retinue, born there first. This is the second station of consciousness.

There are beings uniform in body and diverse in perception, such as the Radiant Gods. This is the third station of consciousness.

There are beings uniform in body and perception, such as the gods of Streaming Radiance. This is the fourth station of consciousness.

There are beings who, having completely transcended the perception of form, with the disappearance of the perception of resistance, not attending to the perception of diversity, thinking Infinite space, have entered and dwell in the base of infinite space. This is the fifth station of consciousness.

There are beings who, having completely transcended the base of infinite space, thinking Infinite consciousness, have entered and dwell in the base of infinite consciousness. This is the sixth station of consciousness.

There are beings who, having completely transcended the base of infinite consciousness, thinking There is nothing, have entered and dwell in the base of nothingness. This is the seventh station of consciousness. The realm of non-perception and the realm of neither-perception-nor-non-perception are the second.

Regarding the first station of consciousness, diverse in body and perception, such as humans, some gods, and some beings in states of woe, if someone understands this, its arising, its cessation, its appeal, its danger, and its escape, is it appropriate for them to take delight in it? No, lord. ...

Regarding the realm of non-perception, if someone understands this, its arising, its cessation, its appeal, its danger, and its escape, is it appropriate for them to take delight in it? No, lord.

Regarding the realm of neither-perception-nor-non-perception, if someone understands this, its arising, its cessation, its appeal, its danger, and its escape, is it appropriate for them to take delight in it? No, lord.

When a disciple, Ananda, having truly understood the origin, passing away, gratification, danger, and escape in regard to these seven stations of consciousness and these two realms, is released without clinging, he is said to be one who is liberated by wisdom.

There are, Ananda, eight liberations. What are the eight?

One perceives form internally, and external forms are seen. This is the first liberation.

Perceiving internally the mind is formless, external forms are seen. This is the second liberation.

Being intent only on beauty. This is the third liberation.

Completely transcending the perception of form, with the disappearance of the perception of resistance, not attending to the perception of diversity, thinking Infinite space, one enters and dwells in the base of infinite space. This is the fourth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of infinite space, thinking Infinite consciousness, one enters and dwells in the base of infinite consciousness. This is the fifth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of infinite consciousness, thinking There is nothing, one enters and dwells in the base of nothingness. This is the sixth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of nothingness, one enters and dwells in the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception. This is the seventh liberation.

Completely transcending the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception, one enters and dwells in the cessation of perception and feeling. This is the eighth liberation.

These, Ananda, are the eight liberations. When a disciple, Ananda, can enter and emerge from these eight liberations in forward and reverse order, as he wishes, having witnessed them for himself through direct knowing in this very life, and having attained to the mental and wisdom liberation, he is called a disciple who is liberated in both respects.

And this, Ananda, is called the liberation in both respects, beyond which there is none other.

There is no liberation superior or more excellent than this.

DN15

DN15: Rejecting Venerable Ānanda’s claim to easily understand dependent origination, the Tathagata presents a complex and demanding analysis, revealing hidden nuances and implications of this central teaching.

Dependent Origination as Energy Flow: The Fire Analogy

The twelve links of dependent origination (paṭicca-samuppāda) are often described as sequential causes leading to suffering, birth, and death. While they are usually explained in causal terms, another way to understand them is as a dynamic flow of energy, where each link fuels the next like piles of burning wood, continuously sustaining the stream of mind-body processes. This perspective highlights both the continuity of conditioned existence and the possibility of reversal through practice.

1. Ignorance (avijjā) – the spark of fire

Ignorance is the starting energy that conditions volitional formations.

-

Functionally, it is the initial spark that sets the causal fire in motion.

-

Ignorance fuels volitional formations (saṅkhāra) by creating tendencies to act out of craving, aversion, and delusion.

Reversal: Ignorance can be extinguished through insight into non-self, impermanence, and unsatisfactoriness, which stops the initial spark from generating further fuel.

2. Volitional formations (saṅkhāra) – adding fuel to the fire

Volitional formations are intentional actions that shape karma.

-

Each intention driven by desire or aversion is like adding wood to the fire, giving the process momentum.

-

These karmic seeds determine the conditions of consciousness (viññāṇa) and the arising of the next life.

Reversal: By letting go of greed and aversion and cultivating the Noble Eightfold Path—right view, right intention, right mindfulness, and right concentration—volitional formations lose their momentum. When the mind acts without craving or clinging, intentions no longer generate new karmic fuel, and the causal continuity begins to fade.

3. Consciousness (viññāṇa) – the flickering flame

Consciousness is the stream of awareness that arises conditioned by past volitional formations.

-

It is the flame itself, momentary yet continuous, always dependent on previous energy.

-

Consciousness fuels nama-rupa, sustaining the mind-body process across moments.

Reversal: Consciousness can be purified through mindfulness and insight, disrupting unwholesome patterns of attention. Concentrated attention on impermanence and non-self reduces the “fuel” flowing into nama-rupa.

4. Name-and-Form (nāma-rūpa) – the body of the fire

Nama-rupa, the combination of mental and physical processes, is the structure that sustains the flame.

-

Without nama-rupa, consciousness has no field for arising.

-

Nama-rupa continuously arises and ceases, conditioned by consciousness.

Reversal: Nama-rupa can be “extinguished” through not conceiving, seeing that mind and body are impermanent and empty of self. Meditation and insight weaken attachment to the aggregates, interrupting the energy that sustains the flame.

5. Six Sense Bases (saḷāyatana) – the conduits of energy

The six sense bases—eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind—allow contact with the world.

-

They channel energy from nama-rupa into experience, producing contact and feeling.

-

Each sense base is continuously recreated along with mind and body.

Reversal: By restraining the senses and cultivating mindfulness, the flow of energy through the bases can be moderated. The mind stops automatically reacting to sense impressions, reducing the “fuel” for craving.

6. Contact (phassa) – ignition points

Contact is the moment where sense bases meet objects.

-

It is the point where potential energy sparks experience, leading to feeling.

-

Without contact, craving does not arise, and the chain slows.

Reversal: Through mindful observation and equanimity, contact no longer automatically ignites craving. Awareness prevents automatic reaction.

7. Feeling (vedanā) – heat of the flame

Feeling, pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, arises from contact.

-

Feeling adds energy to craving, fanning the flame.

-

Positive or negative experiences trigger further mental activity.

Reversal: By abiding in feeling without proliferation, observing feelings as impermanent, craving loses its energy. The flame cools.

8. Craving (tanhā) – fuel for becoming

Craving is the active desire for continued existence or enjoyment.

-

It adds substantial fuel, propelling the flow toward clinging and further becoming.

-

Craving can be subtle or strong, but it determines the intensity of future rebirths.

Reversal: By non-attachment and insight into impermanence, craving can be extinguished. Mind trained in letting go does not feed the fire.

9. Clinging (upādāna) – concentrated fuel

Clinging is attachment to ideas, forms, or existence.

-

It is the densest part of the fuel pile, concentrating energy into continued cycles of becoming.

-

Strong clinging ensures that the next links: becoming, birth, and suffering—are fully powered.

Reversal: Clinging is reduced through insight, ethical discipline, and renunciation. Seeing that nothing is self or worth clinging to reduces the intensity of the fire.

10. Becoming (bhava) – the sustained blaze

Becoming is the momentum of existence conditioned by craving and clinging.

-

It represents the energy of ongoing life, the ready-to-ignite pile of fuel for the next birth.

-

The “flame” of bhava sustains rebirth, moment-to-moment or from life to life.

Reversal: Becoming can be weakened by disrupting craving and clinging, allowing the momentum to cool, eventually leading to cessation.

11. Birth (jāti) – sparks igniting new flame

Birth is the arising of a new mind-body process.

-

The energy accumulated through past links manifests as a new stream of aggregates.

-

Birth is the visible ignition of the previous causal fuel.

Birth does not only mean the literal birth of a being. In the deeper, experiential sense taught in dependent origination, it refers to the arising of a new mind-body process each time identification forms.

In that instant of birth, a new “being” is born: a self is constructed around that mental state. “I am angry,” “I am pleased,” “I am thinking.” A new nama-rupa arises, a new configuration of body and mind expressing that identification.

The moment passes, the identification fades, the “self” of that moment dies. Another contact arises, another feeling, and the cycle begins again.

So in a single day, countless births and deaths occur as the mind continually creates and abandons new identities through craving and clinging.

Reversal: Seeing this process clearly is what weakens the illusion of continuity and self. When mindfulness becomes strong, the mind stops giving birth to these momentary selves—the fire of becoming cools, and the process begins to end even within this life.

12. Aging and Death (jarā-maraṇa) – the eventual burnout

Aging and death are the natural cooling and ceasing of the flame.

In the same way that “birth” happens moment to moment as the arising of a new mind-body configuration around identification, “decay and death” can also be understood in the immediate, experiential sense rather than only as physical death.

When a state of mind arises through contact, feeling, and clinging, a small “self” is born. As attention and craving sustain it, that state begins to age; its energy wavers, the clarity fades, and the feeling dulls or sharpens depending on its nature.

Eventually, the supporting conditions lose strength and the state collapses, passing away like a flame running out of fuel. The “I” that was angry, pleased, or afraid dies, and if craving grasps the next moment, another birth begins.

When the mind resists this fading, sorrow, lamentation, and despair appear, but when the fading is seen clearly and accepted, the fire of becoming cools. In this way, decay and death are not only events at the end of life but a continual dissolution of each self-state, happening with every moment of letting go.

-

Even death is a process, with the momentum of mind-body processes conditioned by previous fuel.

-

If craving or clinging remains, the fire continues into the next cycle of rebirth.

Reversal: Once birth has arisen, decay and death inevitably follow, for whatever is born must cease. Yet for the Arahant, who has ended craving and clinging, no new birth occurs. When the remaining aggregates dissolve, there is no further arising, for all fuel:ignorance, craving, and clinging—has been completely extinguished, and the flame no longer finds a place to ignite.

Conclusion

The twelve links of dependent origination can be seen as a flowing, organic energy system, where each link fuels the next like burning wood. This perspective emphasizes:

-

The moment-to-moment conditionality of existence.

-

How craving, clinging, and ignorance actively “add fuel” to the cycle of suffering.

-

The possibility of reversing the process at each stage through mindfulness, insight, ethical conduct, and renunciation.

In this model, liberation is not about destroying one link in isolation, it is about gradually removing fuel at each stage, so that the fire of conditioned existence naturally dies out.

Dependent Origination

Whoever sees Dependent Origination sees the Dhamma; whoever sees the Dhamma sees Dependent Origination.

MN28

Dependent Origination is the Tathagata's map of how suffering arises. It provides a deep insight on how we can become free of suffering. Understanding dependent origination is the key to understanding how reality is constructed and can be deconstructed. This understanding must be experiential, not just conceptual.

It’s amazing, master … how deep this Dependent Origination is, and how deep its appearance, and yet to me it seems as clear as clear can be!

Don’t say that, Ānanda … Deep is this Dependent Origination, and deep its appearance. It’s because of not understanding and not penetrating this teaching that this generation is not liberated

DN15

SN12.2: The Tathagata teaches monks about dependent origination, explaining it as a sequence starting with ignorance and leading to suffering through various stages including formations, consciousness, name-and-form, the six sense bases, contact, feeling, craving, clinging, becoming, birth, and finally aging and death. Each stage is defined in detail, such as different types of becoming, clinging, and craving. The Tathagata emphasizes that understanding and ceasing ignorance can lead to the cessation of this entire process and thus end suffering.

The Truth - Real Dependant Origination

By: Chinese Aranhant

For a long time, people have been confused by two illusions, one about "matter" and the other about "consciousness." These two illusions, like thick fog, have blinded people's eyes, preventing them from seeing the truth of the world, and trapping them in endless darkness without realizing it.

To facilitate understanding, let's start by discussing the principle of a television. Traditional televisions are typically composed of a television station broadcasting radio waves, which excite the antenna of the television, generating an electric current.

This current, after being processed by various internal components of the television, controls the display screen to emit light. In other words, this process is composed of radio waves, antennas, electric current, components, display screens, and light.

Clearly, these six things are all different: radio waves are invisible electromagnetic waves; television antennas are usually two metal rods; electric current is the flow of electrons in wires; components are image processing units composed of various circuits; display screens are either fluorescent screens or liquid crystal displays; and light is visible electromagnetic waves. They are all completely different things.

Although the changes in light on the display screen are determined by radio waves, people cannot learn anything about the real appearance of radio waves, antennas, electric current, components, or display screens solely from the light emitted by the display screen. Why is that? It's because radio waves do not enter the television; they only interact with the antenna, exciting electric current as a new phenomenon within the antenna.

Electric current is neither the radio wave itself nor the television itself, so people cannot learn anything about radio waves or antennas from electric current alone. The electric current, after being processed by components, does not simply fly out of the display screen; it only interacts with the display screen to produce light as a new phenomenon.

Light is likewise not electric current itself or the display screen itself; it is a completely new phenomenon. People cannot learn anything about the real appearance of the display screen or electric current solely from the light.

Furthermore, they cannot learn anything about the real appearance of radio waves and antennas from the light either. In other words, the relationship between radio waves (A) and antennas (B) producing electric current (C) is not A + B = A or B, nor is it A + B = AB; it is A + B = C. Electric current (C) is a phenomenon completely different from radio waves (A) and antennas (B). If the result were A, B, or AB, people might be able to discern some approximate characteristics of A or B from the result.

But in reality, the result is electric current (C), a completely different phenomenon, so people cannot learn anything about the real appearance of radio waves (A) or antennas (B) solely from electric current (C). The same applies to the relationship between electric current (C) and display screen (D) producing light (E); people cannot learn anything about the real appearance of electric current (C) and display screen (D) solely from light (E), let alone about the real appearance of radio waves (A) and antennas (B).

This principle is quite evident because when people watch TV, they are certainly not seeing the appearance of radio waves, antennas, electric current, wires, and so on.

Our vision is very similar to the principle of a television, where the eyes act like antennas. When light rays from a light source or reflected by objects reach our eyes, they react with the photoreceptor cells in the eyes, generating bioelectric currents in the visual nerves. After being processed by the brain, these bioelectric currents result in visual perception. This process is roughly composed of light, eyes, bioelectric currents, the brain, and visual perception.

These five components are also distinct: light is visible electromagnetic waves; the eyes consist of the eyeball, blood vessels, nerves, and other bodily tissues; bioelectric currents are generated by changes in cell potential and polarity within the body; the brain generally refers to the brain and spinal cord; and visual perception is a form of consciousness. They are all completely different things.

Similar to the generation of electric current from radio waves and antennas, light interacts with photoreceptor cells in the eyes to stimulate bioelectric currents. Bioelectric currents are neither light nor the eyes; they are a completely new phenomenon distinct from both light and the eyes. Similarly, from bioelectric currents alone, we cannot learn anything about the real appearance of light or the eyes.

When bioelectric currents are processed by the brain to create visual perception, visual perception is not bioelectric currents or the brain; it is a completely different phenomenon distinct from them. We cannot learn anything about the real appearance of bioelectric currents or the brain from visual perception alone. This is quite evident because the things we normally see are not the appearance of bioelectric currents or brain tissue, are they? Following the earlier reasoning, it is even more impossible for us to learn anything about the real appearance of light and eyes solely from visual perception.

The problem lies here: people do not consider the light emitted from the display screen to be the real appearance of radio waves or the television itself, yet they assume that what our vision reflects is the real appearance of light.

However, just as what is displayed on the television screen is not the radio waves or the antenna but only the light itself, our perception of what we "see" is actually only the perception itself, not the appearance of light or the eyes.

Although vision is produced by the interaction of light and the eyes, regardless of what light and the eyes look like, we cannot learn anything about their real appearance solely from vision.

Besides vision, we also have hearing, smell, taste, and touch, and the principles of these four forms of consciousness are the same. When the ear interacts with sound, the nose with smell, the tongue with taste, and the body with objects, bioelectric currents are generated.

After passing through the brain, these currents result in hearing, smell, taste, and touch. We similarly cannot learn anything about the real appearance of the senses or the things they come into contact with solely from these forms of consciousness. What we know is actually just hearing, smell, taste, and touch themselves, and these forms of consciousness only reflect consciousness itself, not the appearance of the senses or things.

It's like the combustion of fuel and oxygen producing flames. Regardless of what fuel and oxygen look like, we cannot learn anything about their real appearance solely from the flames, as the flames only reflect their own appearance. However, people always assume that what they normally know is the real appearance of matter, which is the illusion people have about matter.

But for ordinary people, even if they understand the principles mentioned earlier, it is difficult to accept because if this is really the case, it would cause confusion and lead to doubt about whether the world is virtual or real. The reason is that people also have another illusion, the illusion of consciousness. It is precisely because of this illusion of consciousness that people find the illusion of matter to be very reasonable. So, what is the illusion of consciousness?

I've previously discussed the five types of consciousness in humans, namely vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. In addition to these, there's another form of consciousness that doesn't require real-time external stimuli; it's the inner thoughts generated by the mind (brain) and events. For now, let's call it "consciousness of thoughts."

Therefore, humans have a total of six types of consciousness (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and consciousness of thoughts), generated by six types of sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind or brain) and their corresponding stimuli (light, sound, smell, taste, touch, and events).

Let's start with the principle of a television. As mentioned earlier, the light of a television screen is jointly produced by the television and electromagnetic waves. So, when light appears, it indicates that the television and electromagnetic waves have successfully interacted.

Clearly, it's not the light that sees the television and electromagnetic waves; rather, the light depends on them for its existence. The television and electromagnetic waves are prerequisites and causes for the generation of light; light is the product or result of the television and electromagnetic waves. The same principle applies to vision; the eyes and light produce vision. It's not that vision sees the eyes and light, or that the eyes see the light. Instead, vision relies on the eyes and light for its existence. The eyes and light are prerequisites and causes for the generation of vision; vision is the product or result of the eyes and light.

This logic extends to hearing, smell, taste, touch, and consciousness of thoughts. It's not consciousness that actively perceives the senses and objects. Through the previous analysis, it's clear that when consciousness is produced by the senses and objects, it's merely the result of their interaction—a new, independent, non-autonomous, non-living, and passively generated natural phenomenon. When consciousness arises, the fact of awareness has already been established, and the senses and objects have already had their impact.

This consciousness doesn't need to go back to being aware of the objects, nor is it possible to be aware of other objects. This is because when other consciousness arises, it's also due to the presence of conditions involving other senses and objects. The generation of these consciousness types doesn't require an active knower or known objects; the entire process is simply A + B = C.

Whether people like it or not, when conditions involving both the senses and objects are present simultaneously, this process naturally occurs. There's no need to add anything else to actively see, hear, smell, taste, touch, or think. It's similar to the combustion of fuel and oxygen, which results in a flame. When the flame appears, it signifies that the combustion phenomenon has occurred. There's no need to add another active burner; the flame is simply the result of the interaction between fuel and oxygen. Likewise, the entire combustion process is just fuel + oxygen = flame.

So, whether it's within or outside consciousness or the body, there's nothing that possesses the function of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, or thinking. These consciousness types are only naturally generated, new, independent, non-autonomous, non-living, and passively generated phenomena produced by the interaction of the senses and objects. When these consciousness types arise, that's when seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking happen.

The relationship among them is like that of a television or movie; when light appears, it's when the program content appears. They are two sides of the same coin. In the same way, when vision arises, it's the arising of what is seen; when hearing arises, it's the arising of what is heard; when other forms of consciousness arise, it's the arising of what is known in those forms.

However, people are ignorant of this and mistakenly divide consciousness into two parts, thinking that consciousness is one thing, and content is another, connected by the function of awareness. This leads to the misconception that consciousness can be aware of objects. Based on this misconception, most people consider the objects they perceive as real, while some believe that the perceived objects are false or illusions. Regardless of whether they consider the perceived objects as real or false, these viewpoints are built on the illusion that consciousness or something else can be aware of objects.

Now, let's summarize: consciousness doesn't have the capacity for awareness, and there's nothing else that possesses this capacity. The content of awareness is also not the objects themselves.

Both consciousness and the content of awareness are simply new phenomena generated when the senses and objects interact, much like how wood burning produces flames. Flames are indeed produced by wood, but before combustion, flames don't exist within the wood, and after combustion, flames aren't stored anywhere. During combustion, flames take on various shapes and colors in the presence of various conditions, none of which reflect the characteristics of the wood itself. They are entirely independent and new phenomena.

Our consciousness shares this characteristic. Although it's generated by the senses and objects, it doesn't exist before its generation or persist after its disappearance.

At the moment of its generation, consciousness and its content don't reflect any other objects; consciousness is simply consciousness, independent and new. Therefore, rather than saying our senses or consciousness are cognizing objects, it's more accurate to say that the senses and objects together create an entirely new world of consciousness, and this conscious world is all that we know. It includes everything we see, hear, smell, taste, touch, and think about at this moment, including the senses and objects, as well as this article you are reading right now.

However, this doesn't mean that the world is idealistic. Just as when we watch a movie in a theater, we only see the light reflected by the movie screen, but we cannot say that the movie itself consists only of that beam of light. Similarly, even though we only know consciousness, it doesn't mean that the entire world is just consciousness. In fact, the senses, objects, and consciousness are interdependent.

If one of them disappears, the other two cannot exist, much like light, heat, and flames, or like a three-legged stand formed by three wooden sticks. All of this is created by various conditions and gives rise to new phenomena through interaction. This is precisely what ancient enlightened individuals meant by "dependent origination."

The term "dependent origination" doesn't refer to two sticks being put together to make chopsticks, nor does it refer to wood and planks forming a table because these are just names for things combined together, not the generation of something new.

True "dependent origination" refers to the creation of new phenomena, such as wood and oxygen burning to create flames, a drumstick striking a drumhead to produce sound waves, or the eyes and light coming into contact to create vision, and so on.

In the scientific community, it's commonly believed that the material in the universe is independent, and consciousness of life is also independent. The material world existed before the emergence of life. In occasional cases, matter came together to form life, and through evolution, life developed consciousness.

If one day, the material world experiences a major catastrophe, life might disappear entirely, and the universe would return to a state with only matter. However, if someone understands what I've discussed earlier, they'll realize that the world we know is actually co-produced by matter and the senses. Whether matter or the senses disappear, the corresponding world also disappears.

It's like the shadow left on the ground when sunlight shines on a big tree. Whether the sunlight disappears or the tree disappears, the shadow disappears as well. This is what the ancient enlightened individuals meant by "dependent cessation."

These are all part of the fundamental workings of the world. When there are eyes and light, there's vision. When vision arises, the corresponding sensations, thoughts, thinking, and cognition also arise. When there are no eyes or light, there's no vision, and the corresponding sensations, thoughts, thinking, and cognition do not arise. Similarly, this applies to other forms of consciousness. When there are senses and objects, there's consciousness. When consciousness arises, the corresponding sensations, thoughts, thinking, and cognition also arise. When there are no senses or objects, there's no consciousness, and the corresponding sensations, thoughts, thinking, and cognition do not arise.

Only when people truly understand that consciousness arises from the interaction of the senses and objects can they avoid believing that the world is either illusory or real. By observing thinking from the perspective of "when this arises, that arises; when this ceases, that ceases" instead of falling into one-sided thinking about the world's existence or non-existence, its reality or unreality, can they eliminate doubt, further discover the complete truth of this world, increase genuine wisdom, remove ignorance, and embark on the path to true liberation.

About the teaching of Dependent Origination

When people teach about it or quote it, it sounds so good and well arranged: with the arising of this, that must arise in succession; this ceasing that ceases, and so on and so forth runs the whole chain or cycle.

But what is not made clear is where and how to cut the cycle. Where do we cut it off to attain the first stage of enlightenment? Where do we cut it to realize the second stage or the third stage of enlightenment? They say that if we cut out a condition or link in the chain, the cycle breaks. It is so easy to say, but that doesn’t let go of the defilements—it can’t be done like that.

When they teach it, they describe all the steps of arising: dependent on this arises that; dependent on becoming arises birth... I don’t know why they run through it like this, memorizing and writing about it. Apparently, if we cut the chain at becoming, then there will be no more birth, but how do we do this?

In practice, we have to develop moral virtue, concentration and wisdom so as to let go of our identification with the body and mind as being our 'self ’. This is what breaks the chain. We practice to weaken and let go of the defilements of greed, anger and sensual desire. These defilements arise from our deluded attachment to the body as being the self. So to let go of the defilements, we must contemplate the body.

Right view, right view, it is said, venerable sir. To what extent, venerable sir, is there right view?

This world, Kaccāna, for the most part depends upon a duality: upon the notion of existence and the notion of nonexistence.

But for one who sees the origin of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of nonexistence in regard to the world. And for one who sees the cessation of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of existence in regard to the world.

This world, Kaccāna, is mostly bound by attachment, insistence on identity, and adherence to this very attachment as mine: believing this is myself.

But one does not take up, does not cling, does not consider this is myself; does not doubt or hesitate, understanding with wisdom that suffering arises and suffering ceases.

To this extent, Kaccāna, there is right view.

Everything exists, Kaccāna, this is one extreme. Nothing exists, this is the second extreme. Without veering towards either of these extremes, the Tathāgata teaches the Dhamma by the middle:

With ignorance as condition, formations; with formations as condition, consciousness ... thus is the arising of this whole mass of suffering.

With the cessation of ignorance, comes cessation of formations; with the cessation of formations, cessation of consciousness ... thus is the cessation of this whole mass of suffering.

SN12.15

AN11.9: The Saddhasutta recounts a teaching by the Blessed One to Venerable Saddha at Nātika. The Tathagata compares two types of contemplation: that of a wild colt and a thoroughbred. A wild colt, tied to a post, focuses solely on fodder, symbolizing a person overwhelmed by sensual desires and other mental obsessions, unable to see beyond immediate gratifications. In contrast, a thoroughbred, also tied, contemplates broader responsibilities and duties, representing a noble person who transcends sensual desires and mental obsessions, understanding the true nature of things and meditating without attachment to worldly elements or perceptions. This noble person is revered by celestial beings for his profound practice, which is independent of any worldly support.

DN15: Rejecting Venerable Ānanda’s claim to easily understand dependent origination, the Tathagata presents a complex and demanding analysis, revealing hidden nuances and implications of this central teaching.

MN38: The great discourse on the destruction of craving starts out describing how consciousness is dependently originated and how to bring about the cessation of craving. It then describes in detail the gradual path.

MN141: The Tathāgata delivers a brief statement of the Four Noble Truths. Then Venerable Sāriputta expands upon it in detail, making this sutta one of the most complete teachings on the Four Noble Truths. Venerable Sāriputta shows how everything tied to the five aggregates is dukkha: The body is subject to birth, aging, and death. Pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral feelings are all impermanent. What we perceive changes over time. Awareness depends on external conditions and is not permanent. Venerable Sāriputta explains that The Root of Suffering is craving, the fuel for rebirth. The mind constantly grasps at things, creating attachment and suffering. Craving arises from ignorance—not understanding that everything is impermanent. Venerable Sāriputta describes Nibbāna as the complete cessation of craving. It is not a state of nothingness, but the freedom from all suffering and attachment. It is beyond birth and death—a state of peace and liberation. Nibbāna is not something one “attains” but the realization of the cessation of craving. Venerable Sāriputta breaks down each factor of the Eightfold Path, explaining how they work together. Right View: Understanding suffering, impermanence, and non-self. Right Intention: Developing renunciation, goodwill, and compassion. Right Speech, Action, and Livelihood: Establishing ethical conduct. Right Effort, Mindfulness, and Concentration: Training the mind to let go of craving.

SN12.23: The Tathagata teaches that the destruction of taints is achieved by those who know and see the true nature of form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness, including their arising and cessation. He emphasizes that the knowledge leading to the destruction of taints is conditioned by liberation, which in turn is supported by a sequence of conditions: dispassion, disenchantment, knowledge and vision of things as they are, concentration, happiness, tranquility, joy, rapture, faith, suffering, birth, becoming, clinging, craving, feeling, contact, the six sense bases, name-and-form, consciousness, and ultimately ignorance. Each step is necessary for the subsequent one, illustrating a cascading effect similar to rainwater flowing from mountains to the ocean.

SN12.38: Intentions, plans, and latent tendencies sustain consciousness, leading to future existence and suffering, including birth, aging, and death. However, if one eliminates intentions, plans, and latent tendencies, consciousness does not continue, preventing future existence and the associated suffering. This cessation of consciousness halts the cycle of suffering.

SN12.51: A desciple should thoroughly investigate the causes of suffering in accordance with dependent origination. If someone who still has ignorance makes a choice, their consciousness fares on to a suitable state of existence. But one who has eradicated ignorance is detached and is not reborn anywhere.

SN22.64: In Sāvatthī, a disciple asked the Blessed One to teach him the Dhamma briefly to help him remain diligent. The Tathagata explained that conceiving binds one to Māra (the Evil One), while not conceiving frees one. The disciple affirmed his understanding, interpreting that conceiving elements like form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness binds one to Māra, whereas not conceiving them leads to liberation. The Tathagata confirmed this understanding was correct, and the disciple achieved the state of an arahant.

SN35.30: The Tathagata teaches disciples the path to eradicate all conceit, emphasizing non-attachment to sensory and mental processes. He instructs not to conceive of the eye, forms, eye-consciousness, or any sensory or mental phenomena as 'mine.' This detachment extends to all senses, including the mind, where no phenomena or arising feelings are conceived as personal possessions. By not conceiving or clinging to anything, a disciple does not tremble and ultimately achieves final Nibbāna, understanding that the cycle of birth is broken and the spiritual journey completed. This teaching is presented as the path to fully eradicate all forms of conceit.

SN35.31: The text teaches disciples the path to eradicate all conceit, emphasizing non-attachment to sensory and mental experiences. It instructs disciples not to conceive of sensory organs (like the eye or tongue), their functions, or the sensations they perceive as "mine." By not identifying with these experiences, one avoids attachment, which leads to agitation and rebirth. The ultimate goal is to achieve Nibbāna, realizing that one has lived the holy life fully and there is no further state of being to attain. This path is presented as the way to completely eradicate conceit.

SN35.248: In the Sheaf of Barley Discourse, the Tathagata compares an uninstructed person's experience of sensory phenomena to a sheaf of barley being repeatedly struck by flails, illustrating how such a person is impacted by both agreeable and disagreeable sensations. The discourse also recounts a battle between the devas and asuras, where Vepacitti, the lord of the asuras, is bound when he considers the asuras unrighteous and the devas righteous, and freed when his perspective shifts. The Tathagata uses these stories to emphasize the bondage created by personal conceits and thoughts, urging disciples to train their minds to be free from such mental proliferations, which he describes as diseases, tumors, and darts. The overarching message is to cultivate a mind free from the agitations and bindings of personal identity and speculative thoughts.